The introduction of the new Optane family of memory drives comes after years of development and promise to bury the traditional hard drive. In fact, Intel seemed to indicate that its non-volatile XPoint 3D memories might even make it difficult for successful SSDs.

Things are not so clear now that the first units have reached both the business market and the end user market. At least in the second case we find small units and whose advantages, no matter what Intel says, show no revolution in the current market. It seems rather that Intel wants to invent a solution to a problem that (already) does not exist.

Caching is gerund

Intel’s own engineers pose their end-user solution as a solution to act as a cache of a more traditional storage system thanks to Rapid Storage Technology controllers. This raises some barriers, such as being supported only on Windows 10 64 bit and only for the boot partition.

That implies that these Optane memories of 16 GB ($44) and 32 GB ($77) for end users – the story could change for business units – are geared to serve as “accelerators” to make the operating system and applications more frequently used are more fluid.

Although, as indicated in AnandTech, reading performance is fantastic (1200 MB / s), things clearly get worse in scripts (280 MB / s), but it is true that this orientation to frequent operations caching makes that imbalance not so important.

Welcome to a new term: Tail depth

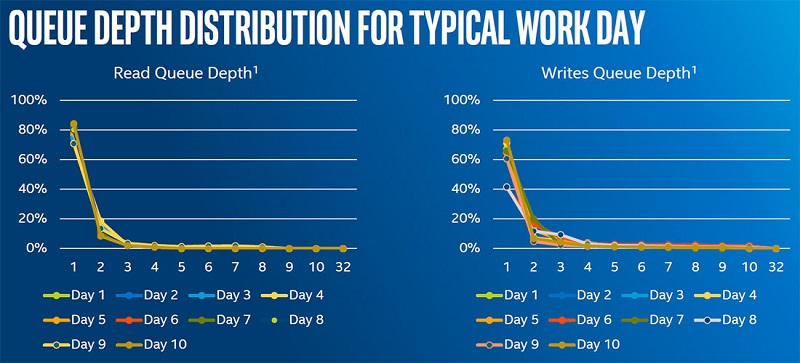

To defend the validity of the idea, in Intel we are talking about a term that had been little handled in technical analysis: queue depth (Queue Depth, QD), which indicates the number of pending I / O requests) That can be “queued” at the same time in a storage controller.

As explained in LegitReviews, Intel provided a series of studies assessing what type of tail depth different types of applications and operations were, and in that graph, it was shown that the low tail depths were much more important than the high ones In most read and write operations. Over time, Intel’s studies revealed, most operations are between QD1 and QD4.

That’s where the real benefit of the Optane memories is: they behave fantastically in those low QDs, in front of a hard disk that suffers in those situations. That is why Optane makes sense for Intel in those scenarios where according to Intel can achieve up to 14 times the performance of traditional drives, and are also superior to conventional SSD and even attractive M.2 NVMe drives. Caution: this is data from Intel, and until Optane’s actual behavior can be assessed (they are out April 24), we have to look at those conclusions with critical sense.

You may also like to read another article on iMindSoft: Intel Core i7-7700K, Core i7 Kaby Lake most powerful resort to 4K as hook for everyone

Use cases: If you only have a traditional disk, good idea

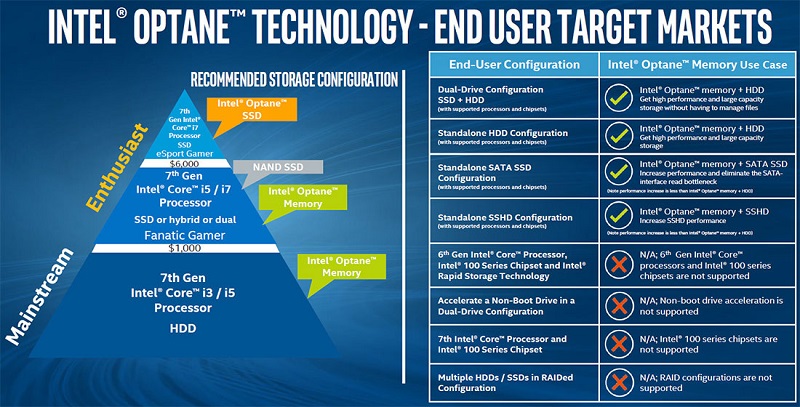

If you look at the use cases proposed by Intel (in the image) you see how the proposal of Optane is oriented mainly to equipment with a traditional hard disk in which this unit could significantly improve the overall behavior of the computer thanks to Those performance readings and its PCIe 3.0 x2 NVMe interface.

The speech, in fact, is very similar to the one that has been realized during the last years with the units SSD. If you do not have such a drive on your computer, updating it to install the operating system on it is a great idea that will allow you to “rejuvenate” it. With Optane the idea is basically the same, but it’s as if Intel was late for the party. If we already have SSDs, why do we need Optane?

According to Intel, this is a cheaper alternative than an SSD. In this way, you could combine a traditional 1 TB HDD with a 32 GB Optane drive and the cost would be less than that of a 1 TB SSD and even 500 GB. It’s something like an evolution of hybrid hard drives that have become famous in Apple teams with its famous Fusion Drive, an option that could be curious in certain scenarios.

The problem with that approach is that you cannot really “upgrade” your computers with Optane. This type of M.2 modules are only available for computers with certain Intel seventh generation processors, and only with some chipsets. Not all motherboard manufacturers will offer compatible solutions, limiting the scope of the solution.

In fact even in the case of having compatible equipment, what do we want Optane? It is very unlikely that someone who buys a computer with one of the new Intel chipsets and processors will install a hard drive as their main drive: M.2 NVD SSD drives are an overly attractive alternative, and prices are not as high. It’s true that if you want to save some money you can choose to combine a traditional hard drive with one of these Optane drives, but do not you rather have an SSD for everything?

The solution that Intel offers us with Optane opens new possibilities, of course, and that is always good. Now it is you who decide. Do you think Optane can be really interesting now that the hard drive is decaying in new batch computers? It may just be that this first move from Intel will help us begin to realize the advantages of memory drives that are certainly interesting, but that would be much more with wider storage capacities. Everything will come (hopefully).